bobtilden.com BACK TO THE FUTUREMay 26, 1999

I thought I was safe, riding along a country road, with one of the raunchier talk shows playing on

the radio. Nothing was likely to challenge the driver, and the radio show was unlikely to engage

me in any serious thought. I have been to enough public restrooms to have read the original

drafts of most shock- jock scripts on the partition walls.

The folks on the radio must have come up for air, because for a moment they talked of how

foolish it is for airports to be located "right in the middle of town", and how dangerous it is for

pilots and populace alike. I thought how silly it was to have built Chicago's Midway airport with a

runway that points exactly to the spot where some day a pair of high rise apartments would be

built.

Silly too, for that matter, to have placed the Elmira airport right in the middle of what would

become the area's most desirable commercial and residential properties. Looking at a 1946

picture, I can see the problem lurking in the expanse of flat, fertile, and well- drained farm land,

broken only by the tiny villages of Horseheads and Big Flats.

My ride ended at Kevin Hooey's airport on a hilltop east of Beaver Dams, where my plane was

parked. Kevin's place does not much resemble Midway airport, or even Big Flats. It is no more

than a huge hilltop hayfield, and unlike most places, it is far quieter now than it was a hundred

years ago.

This year, as winter has turned to spring, I came to notice that a brushy spot beyond the runway

was comprised mostly of lilac bushes. A clump of lilacs, a group of fruit trees, or an occasional

pair of dooryard maples often mark the spot where a house used to stand. The thicket was on my

list of things to investigate someday, and on this morning I had the time.

Sure enough, in the middle of the lilac patch was the stone foundation of a house. As I walked

around it, all alone on the hilltop clearing, I tried to visualize the outline amid the debris that had

been bulldozed into the cellar hole. Continuing my walk, I found the stone- lined well in the

dooryard. I tried to imagine the work that went into digging the well, and how productive it could

have been, sitting on a hilltop where bedrock is only two feet below the clay soil.

I sat on the ground just downwind of the lilacs, listening to the meadow birds and enjoying the

fragrant smells of springtime that were carried on the breeze that was already stirring. How many

times had the fickle promises of springtime blossomed for the people that lived in the house, I

wondered. How many kids played in the yard, and how many grandparents quietly waited out

their last days in the back bedroom? What hopes and heartbreaks, I wondered, had filled the days

in between those years?

I didn't want to leave, but I couldn't stay either. Just like a hundred years ago, there isn't enough

money on the hilltop to pay the bills, so I climbed into the plane and flew down to Elmira for the

day's work. It was such a short trip, but it took me all the way back to the future.

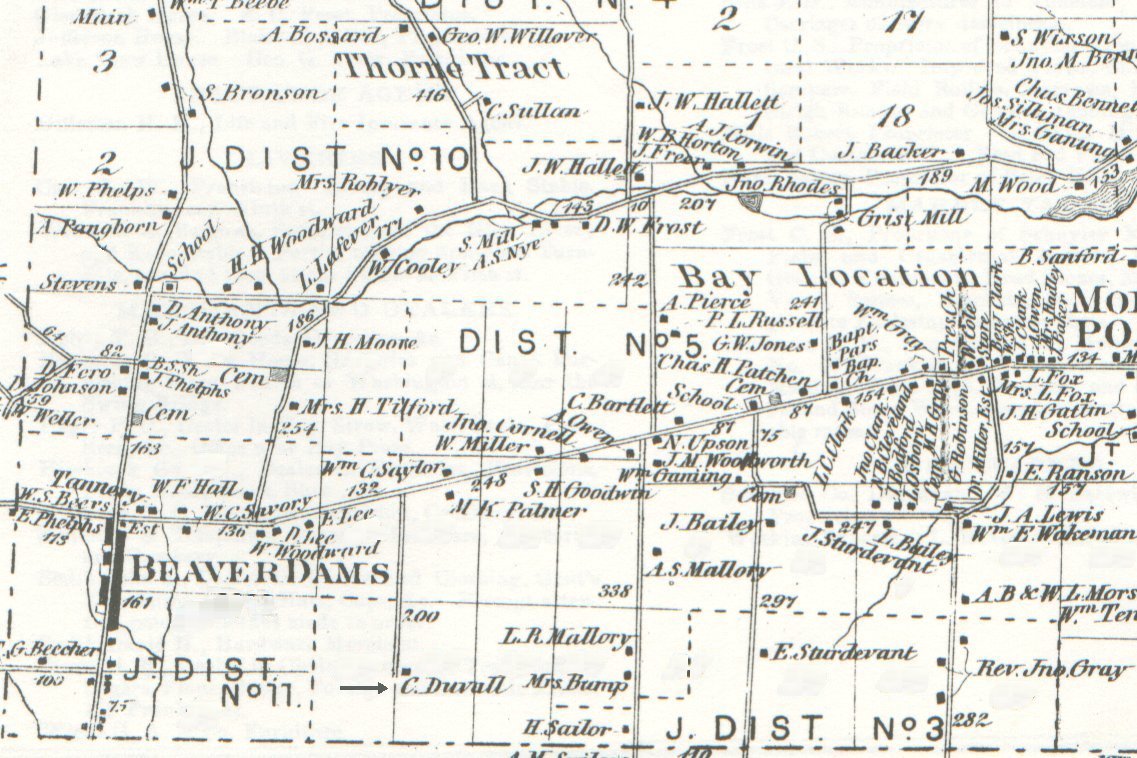

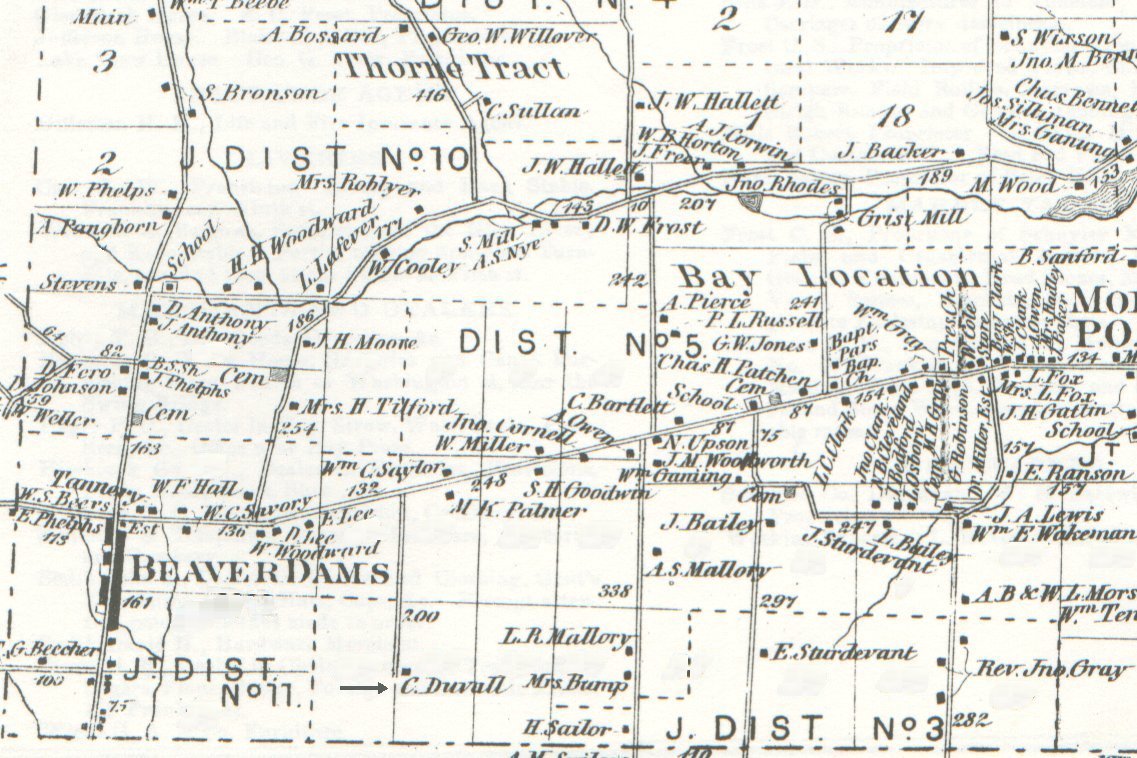

This is the southwest corner of Schuyler County as depicted in an 1874 atlas. The farmstead that I explored is noted as belonging to

"C. Duvall" about one third of the way from left to right across the bottom of the map. Note that it is a long way from anywhere else;

that is a function of the terrain. The present- day airfield is just to the northwest of the Duvall farm, and the main runway parallels

what is now called Duvall Road.

| Plane Talk Archives |

Return to Home Page |

E- mail Bob Tilden at rdtilden@yahoo.com |